Before our arrival via Southampton, a Dutch immigration ship arrived ahead of us, with young men aboard. They had dreams of a prosperous future in this new country. A group of young men shared their three-week passage and became best friends; among them were my two future brothers-in-law.

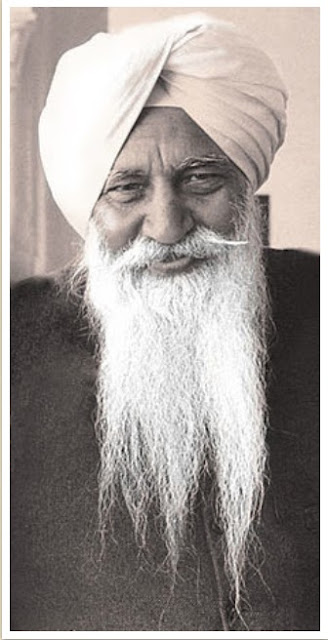

My father in the centre and Willem on the right.

My sisters were born before the war and my dad, an indentured labourer in Germany was away for five years. After his return to the Netherlands, my brother and I were born, creating a gap of ten years between my sisters and us.

Through the Dutch social connections my sisters met Jack and Willem and from then on stayed together for the remainder of their lives.

We had two weddings during this time and later welcomed the first grandchild. My niece became part of our household, as we took care of her during the day with both her parents at work. Linah carried her proudly wrapped onto her back, African style. Three years later the young family returned to Amsterdam. Little did we know that two years later were we would make that same journey.

My eldest sister Riet was married to Jack and remained in South Africa where they started their own business in air-conditioning, refrigeration and cooling systems. Along with building up the business, they added two children to their family.

At that time the cooling systems used asbestos and with the prolonged exposure to that, Jack developed asbestosis in his later part of his life. His wish was to die at home which is not an easy task. Along with a nurse who checked in on him, my brother John came to help out. Willem flew in from Amsterdam to assist with the nursing of his old friend.

I phoned every few days to check on the condition and Jacks well-being. I chatted with my sister who was busy closing down the business which was located in the lower part of the house. She also had a contractor come in to retile the bathroom.

One morning I called and Riet answered, totally in distress and through her sobs she said that Jack had passed away during the night. I said that I would call back later.

During the day I returned the call and Riet answered, laughing. Laughing? I questioned the situation and she explained the following:

Jack’s body has to be removed and they called an ambulance to transport him. The house was surrounded by a ten-foot-high security fence and a gate that was opened electronically from the inside of the house. Willem was placed by the window to watch for the ambulance so that he could open the gate for them. At the same time the contractors arrived with a pick-up truck, two black labourers jumped out, one grabbing the wheelbarrow.

Willem said “ OMG has the system ever deteriorated since I lived here ”

Jack passed away at 72 years old. My sister Riet, six years younger than him, also lived to 72. They had a good life in South Africa and remained Dutch citizens and their ashes returned to the old country.